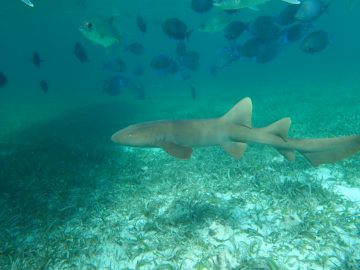

Using computer simulations to peer into the uncertain future of Earth’s oceans, researchers from the Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries (IOF) produced a model that depicts how energy moves up the food web from primary producers – organisms like phytoplankton – to top ocean predators like sharks and tuna.

Using computer simulations to peer into the uncertain future of Earth’s oceans, researchers from the Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries (IOF) produced a model that depicts how energy moves up the food web from primary producers – organisms like phytoplankton – to top ocean predators like sharks and tuna.

Their goal: to see how this energy transfer would change by the last decade of the century under contrasting levels of climate change mitigation.

The findings paint a bleak picture.

They found that in a scenario without effective carbon mitigation resulting in continuous increases in greenhouse gas emissions in the 21st century, the ocean would lose 18 per cent of animal biomass by 2099 relative to the present day, which also means less fish available for people to draw from oceans’ already-limited supply.

The study, published recently in Global Change Biology, took a unique approach that differed from other research examining the effects of climate change on marine life.

“In our model, instead of considering species, we considered the position of the species in the food web,” said Hubert du Pontavice, the study’s lead researcher, who completed the project as part of his PhD at the IOF. “This is very interesting because we have a very simple model and we can predict relatively easily the changes of biomass.”

Du Pontavice collaborated with colleagues studying biology and food webs to make a model of Earth’s oceans that consisted of 40,000 unique “cells” containing climate and biological information.

Du Pontavice collaborated with colleagues studying biology and food webs to make a model of Earth’s oceans that consisted of 40,000 unique “cells” containing climate and biological information.

“It’s huge. It’s a huge quantity of data we had to handle, understand well, and use well,” he said.

Top ocean predators will lose most acutely if governments make no effort to curb greenhouse gas emissions.

“It’s the butterfly effect,” said Gabriel Reygondeau, a co-author of the study and research associate at the IOF who assisted in developing the statistical methods behind the model. “A butterfly in Australia can cause a tsunami in Japan. That’s exactly what we have studied here. The change of temperature alters the production of ocean vegetation. The change could be not that important, but even a minor alteration cascades to a significant perturbation in the food web dynamic and ends up with huge decrease of top predators.”

According to William Cheung, an IOF professor and Canada Research Chair in Ocean Sustainability and Global Change who co-supervised du Pontavice’s project, “we’re already at the maximum capacity in harvesting fish from the ocean… this means we will not be able to get more fish by fishing harder. Meanwhile, climate change is further reducing the ocean’s capacity to support biodiversity and provide fish for human communities.”

Like other modelling that has examined how climate change will impact oceans, the researchers’ simulation predicted that tropical waters will see the greatest reduction in the amount of marine life they contain as fish there die or move poleward. Once again, it is people in tropical countries who are set to lose the most to climate change.

“This research adds to the evidence of previous studies,” Cheung said. “We now have strong evidence that climate change will also impact the ocean ecosystems and we need to tackle these problems for the oceans. Our study underscores it is essential for immediate actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions that can substantially reduce climate impacts in the ocean.”

Tags: climate change, CORU, food webs, Gabriel Reygondeau, IOF students, Marine ecosystems, modelling, Overfishing, research, William Cheung